By Graham Warder, Ph.D., Keene State College

Many disabled Union veterans would not have survived the war without the efforts of the women of the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC). On June 9, 1861, Abraham Lincoln signed an order creating the USSC, but the Sanitary Commission was not a normal part of the burgeoning federal bureaucracy. It was a semi-public organization that gave the government and Union Army advice on modern medical practices, inspected military camps to promote hygiene, helped create a hospital system and an ambulance corps, and even raised money to pay for medical supplies.

The leadership of the USSC was made up of prominent men, among them Henry Bellows, George Templeton Strong, Frederick Law Olmsted, and Samuel Gridley Howe. But much of its most important work was done by women. The very idea of centralized relief originated in April 1861 with the Women’s Central Relief Association of New York City, led by physician Elizabeth Blackwell.

Starting in response to the medical disaster of the First Battle of Bull Run, the Sanitary Commission helped make the Union medical effort far more efficient and effective than that of the South. Under the guidance of the Sanitary Commission, over 15,000 women, including author Louisa May Alcott, volunteered to work, often as nurses, in the nation’s vast system of military hospitals.

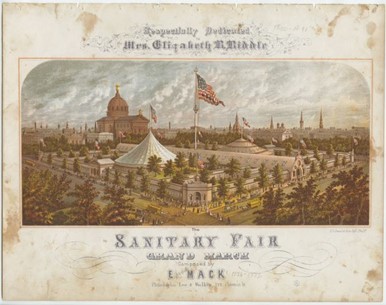

Many other women volunteered to make possible the many Sanitary Fairs that ultimately raised millions of dollars to care for ill, wounded, and disabled soldiers. The Fairs included entertainments and exhibits. They also sold souvenirs and crafts. Such events took place throughout the North and helped to tie the civilian lives of women to the war effort.

The seal of the Sanitary Commission vividly displayed the primacy of women in the work of the organization. A nurse, portrayed as an angel, descends upon a battlefield to rescue injured soldiers. Such imagery suggests that Civil War female benevolence was an important stepping stone toward the full political participation of women in American life. It also suggests, along with the common trope of Union nurse as mother, that disabled veterans might be viewed as childlike, dependent, and incapable of fulfilling the demands of nineteenth-century manliness. Disabled Union veterans, sometimes celebrated as heroes, sometimes demeaned as moochers, would struggle with the mixed meanings of disability for the rest of their lives.

Sources:

Giesberg, Judith Ann. Civil War Sisterhood: The U.S. Sanitary Commission and Women’s Politics in Transition. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2000.

Humphreys, Margaret. Marrow of Tragedy: The Health Crisis of the American Civil War. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013.

Silber, Nina. Daughters of the Union: Northern Women Fight the Civil War. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005.

Stille, Charles. History of the United States Sanitary Commission. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1866. http://archive.org/details/historyofuniteds00stiluoft.