Louisa May Alcott, I Want Something to Do

By Graham Warder, Ph.D., Keene State College

In many ways, Louisa May Alcott (1832-1888) was an extraordinary woman. She was raised in Concord, Massachusetts, among the leading transcendentalist thinkers of the 1830s and 1840s, and she was the author of the best-selling Little Women, published in 1868. Her father, Amos Bronson Alcott, was one of the quirkier reformers of the antebellum period. He was a firm believer in the perfectibility of humanity, and his educational theories, dismissed as hopelessly optimistic in his day, were surprisingly modern. His most radical experiment, though, was a utopian, self-sufficient farming community called Fruitlands that he founded in 1843 in Harvard, Massachusetts. It failed after seven months, and his family almost starved. He was constantly in financial straits, and Louisa May Alcott would turn to writing as a way of making money. She found success and fame with Little Women, a beloved novel loosely based on her own childhood experiences. It has been adapted into four major motion pictures.

In other ways, Louisa May Alcott was typical. She personified the larger cultural forces shaping the Northern middle class in the decades before the Civil War. Little Women is a celebration of nineteenth-century domesticity and the female-centered home. Domesticity, an ideology propounded by influencers like Catharine Beecher in popular advice books, held that women were morally superior to men and that it was the duty of women to create a nurturing, pure, utopian space that would moralize men and children, the home. When the home was threatened by the public sphere and when the economic and political worlds failed to live up to the moral standards of Northern middle-class femininity, it was the duty of women to do something, even if that meant leaving the home.

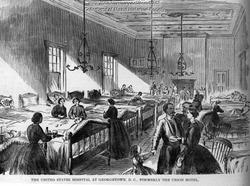

Louisa May Alcott left home in 1862. She spent six weeks working as a nurse at the Union Hospital in Washington, D.C., before contracting typhoid fever and almost dying. Her letters home were collected and revised in Alcott’s first book, Hospital Sketches, published in 1863. The book introduces Tribulation Periwinkle, really Alcott herself, who said, like so many women of the North as the Civil War began to rage, “I want something to do.” Some women sent supplies to their men in uniform, some organized the ubiquitous “Sanitary Fairs” to raise money for the United States Sanitary Commission, and some became Union Army nurses under the supervision of Dorothea Dix, the asylum reformer.

Hospital Sketches describes the journey to Washington. Then, immediately upon her arrival, Tribulation Periwinkle must care for wounded men newly arrived from the Battle of Fredericksburg. She met “a regiment of the vilest odors that ever assaulted the human nose,” and “armed with lavender water,” proceeded to her work. The hospital challenged her womanly sensibilities. Alcott wrote, “The sight of several stretchers, each with its legless, armless, or desperately wounded occupant, entering my ward, admonished me that I was there to work, not to wonder or weep; so I corked up my feelings, and returned to the path of duty.” She learned how to dress wounds, something that did present “a festive scene.”

Alcott was particularly offended by the insensitivity of the male surgeons, who performed amputations without ether. Overall, though, Hospital Sketches is surprisingly upbeat and even humorous. The real experiences of Civil War nurses must have been traumatic. In a letter written to her friend Hannah Stevenson, Alcott wrote that “half a dozen stumps are waiting to be wet & my head is full of little duties to be punctually performed.” This was hardly the world of Little Women.

Alcott’s time as an Army nurse was cut short by a bout of the same illness that took the life of Abraham Lincoln’s son, Willie, in 1862. Typhoid fever rendered Alcott a patient, not a caregiver. In a journal entry for February 1863, she wrote, “Recovered my senses after three weeks of delirium, and was told I had had a very bad typhoid fever, had nearly died, and was still very sick. All of which seemed rather curious, for I remembered nothing of it. Found a queer, thin, big-eyed face when I looked in the glass; didn’t know myself at all; and when I tried to walk discovered that I couldn’t, and cried because my legs wouldn’t go.” Civil War hospitals were clearly dangerous place, both physically and psychically. Alcott’s time in Washington brief, and she seems not have to incurred any lasting disability. Other were not so lucky. Something like post-traumatic stress disorder must have haunted some former nurses. Others were certainly physically disabled because of their service

About 18,000 women worked in Union military hospitals during the war. Most were not of Louisa May Alcott’s relatively privileged status. None received pensions until Congress passed the Army Nurses’ Pension Act of 1892, and even then, the application process required that they prove that they were “morally deserving.”

Sources:

Alcott, Louisa May. Her Life, Letters, and Journals. Boston: Little Brown, and Company, 1898. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/38049/38049-h/38049-h.htm

Alcott, Louisa May. Hospital Sketches. Boston: James Redpath, 1863. https://archive.org/details/hospitalsketches00alcorich/mode/2up.

Letter from Louisa May Alcott to Hannah Stevenson, 26 December 1862, Collections Online, Massachusetts Historical Society. https://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=2168.

Schultz, Jane E. “Race, Gender, and Bureaucracy: Civil War Army Nurses and the Pension Bureau.” Journal of Women’s History 6, no. 2 (1994): 45–69. https://doi.org/10.1353/jowh.2010.0384.

Silber, Nina. Daughters of the Union: Northern Women Fight the Civil War. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005.